Marc Andreessen, a well-known Internet entrepreneur and venture capitalist, once said new technology tends to go through a 25-year adoption cycle.

Part of the reason it takes so long: humans take time to warm up to new technology.

That appears to be true of autonomous vehicles. Three-quarters of Americans say they are afraid of riding in a self-driving vehicle, according to a survey released this year by AAA. More than half (54 percent) say they would feel less safe sharing the road with autonomous vehicles.

At the same time, while the majority fear self-driving cars, many are also seeking out the very same technologies in our next vehicles. AAA’s survey showed that 59 percent of Americans look for autonomous features when shopping for new rides.

Greg Brannon, AAA’s director of automotive engineering, explains the apparent contradiction: “The idea of letting go of the wheel is a scary proposition for drivers.” But when it comes to automatic emergency braking, blind spot monitoring, lane assist, or adaptive cruise control, consumers see those as safety tools, even though they’re developed as components of autonomous vehicles.

Consumers will have some time to get used to the idea, perhaps even as long as the 25 years that Andreessen predicted. But that doesn’t mean drivers get to sit back and relax until then.

Though it will take years for autonomous vehicle technologies to become the norm, “driving skills need to evolve right now.

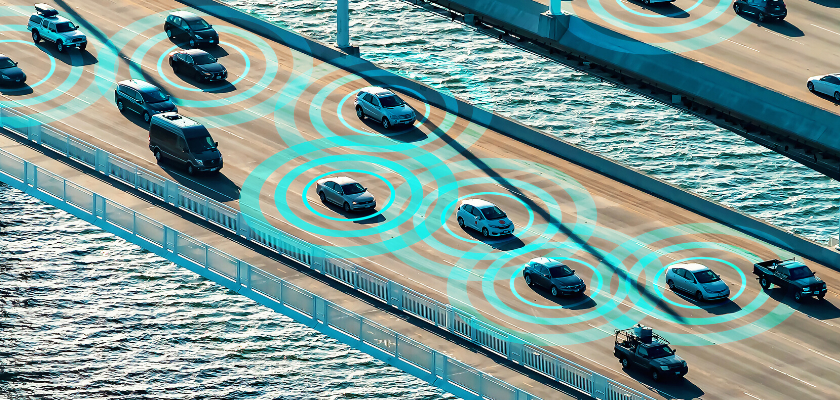

“In fact, driving skills need to evolve right now,” Brannon said in an interview with Lytx. For the next few decades, the world’s roads will be a mix of vehicles with varying degrees of automation. This transition period, from human control to fully autonomous, will require drivers to learn how to safely operate vehicles equipped with new technologies as they roll out.

In some instances, even commercial drivers might rely too much on automated technology, said Lytx VP of Safety Services Del Lisk. In adapting to the steady integration of automated technology into their vehicles, such as lane departure technology, “they may get too comfortable with the technology and take their eyes off the road for extended periods of time,” Lisk said. “We see this occur in our reviewed videos -- the driver may look up when the warning alert sounds, correct the vehicle in the lane, and then return to complacency or distraction. As a vehicle has more driver-assist technologies, drivers may actually take more risks.”

Lisk added, “After a period of time, if a driver continually experiences what he or she believes to be innocuous warnings, they might ignore them altogether. There can be an over-reliance on automated technology that detracts from a driver’s level of engagement on the road. That’s the evolution that is taking place, and we’re using our coaching insights to help safe driving behavior evolve in step with automated technology.”

But there’s another potential hazard on the road to autonomy — the lack of standards. Each manufacturer currently develops its own technologies. As a result, the definition of “safe operating procedure” will vary by vehicle model, potentially creating driver confusion.

“This is a really critical issue,” Brannon said. “The technologies we have today are not implemented the same way by manufacturers. They don’t always function the same way. The only place with reliable information on how to safely operate your specific vehicle is the owner’s manual. That’s the most well-reviewed document by lawyers and engineers, but the least-read book by consumers. Unfortunately, that’s where you get the best information about what your specific vehicle does and what its limitations are.”

Drivers agree. Eight out of 10 people surveyed by AAA said autonomous systems should all work the same way, regardless of who the vehicle manufacturer is.

Another challenge is figuring out what has to happen for drivers to safely resume control of a vehicle as it exits self-driving mode. “How quickly can you go from reading a book to driving your vehicle?” Brannon said. “Our research shows that it takes more than 20 seconds to cognitively re-engage in a task. That’s not an insignificant amount of time. During that time, the vehicle has to provide enough feedback that the driver is certain of what’s expected of them. It can’t just be a chime. There have to be clear instructions.” Those instructions, however, have yet to be defined.

Brannon’s advice to fleet managers for the next few decades: “You should embrace the technology for your own use, but you should also take into account the fact that you’ll be operating in a mixed fleet for decades to come. Some vehicles may be more automated, others less so. As new technologies become available, make sure your drivers know how the technologies work and their specific limitations.”

The bottom line from a safety standpoint? Brannon is optimistic that innovations in autonomous vehicles will decrease the overall risk profile of traveling on our nation’s roads.

“In my experience, autonomous vehicles tend to be much more cautious than normal drivers,” Brannon said. In addition, “autonomous vehicles don’t have road rage. They don’t get inebriated. And they don’t have bad days. My guess is that this will ultimately lead to safer roads.”